Polymer scaffolds are three dimensional templates that mimic the body’s extracellular matrix (ECM) which is a natural network of proteins and sugars around the body that guides cell growth. Tissue regeneration is enhanced by providing structural support and biological signals to promote cell adhesion, proliferation and differentiation. Through a proccess known as remodeling the body asborbs and slowly replaces the ECM with new cells. As such an artificial polymer scaffold designed to function as an ECM needs to be biocompatible and biodegradeable, proteins and peptides are also slowly released with degradation. These biomaterials need to combine tunable mechanical properties with controlled degradation, maintaining mechanical strength in a structure designed to degrade being a primary challenge.

Image credit: Modulating mechanical behaviour of 3D-printed cartilage-mimetic PCL scaffolds

Image credit: Modulating mechanical behaviour of 3D-printed cartilage-mimetic PCL scaffolds

Design Principles for Polymer Scaffolds

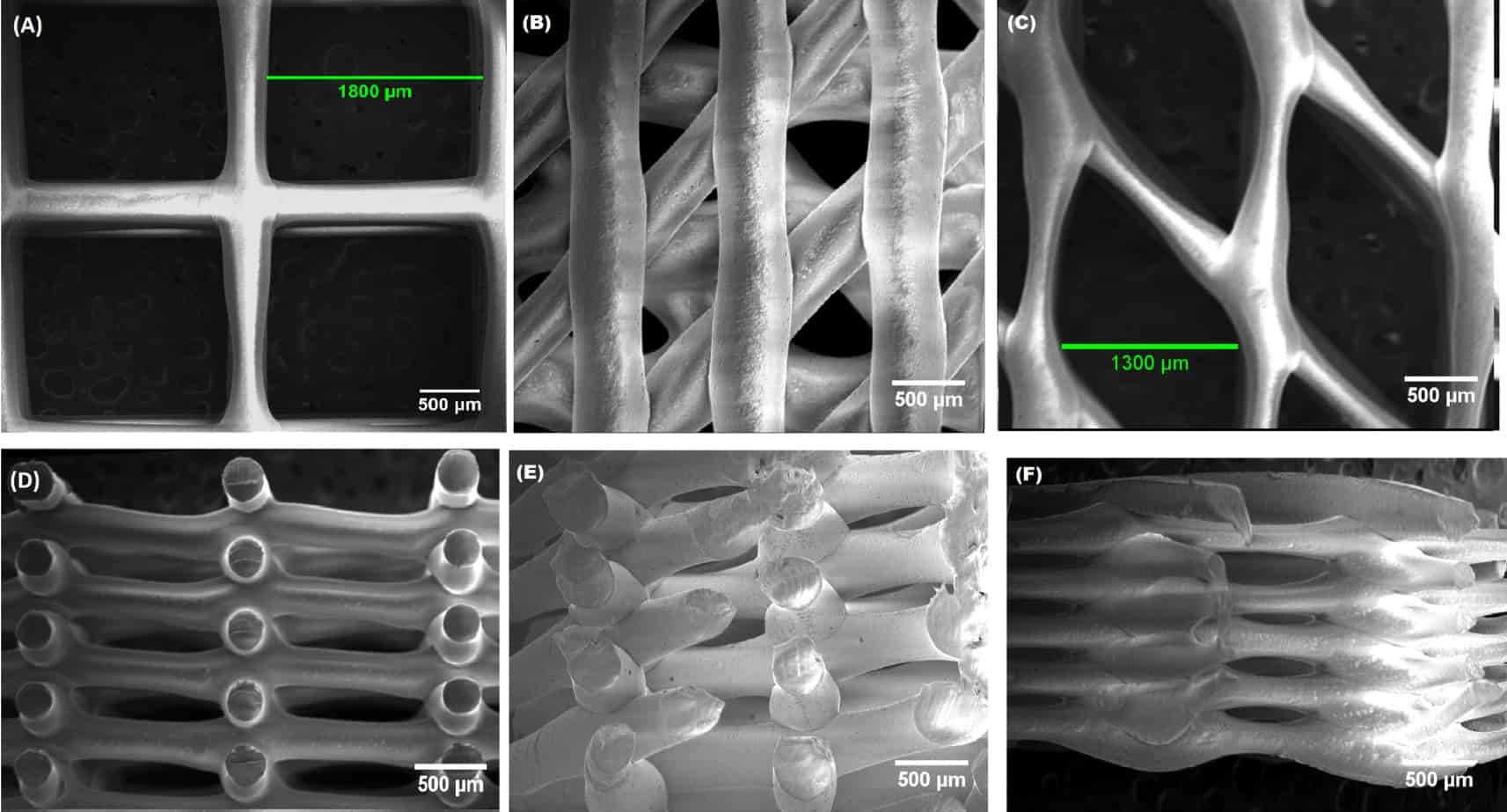

Effective scaffold design requires careful consideration of multiple properties that are interconnected. The scaffold must provide a porous architecture with pores ranging from 20-500 μm to enable cell infiltration, nutrient transport, waste removal and vascularisation. Porosity typically exceeds 90% for 3D poroius scaffolds to accommodate cell growth and tissue formation while maintaining mechanical integrity during the regeneration process.

The scaffold actively guides tissue development through its three-dimensional structure. Its structure affects how cells migrate, proliferate, and organise. Surface topography at the nanoscale level can influence cell attachment and differentiation. For example, fibrous scaffolds are used in tendons and ligaments to mimic their natural anisotropic nature and the highly aligned bundled collagen fibers.

Natural Polymers for Scaffold Fabrication

Natural polymers offer inherent biocompatibility and bioactivity derived from their biological origin. Collagen provides excellent cell adhesion sites through integrin-binding. However, collagen scaffolds typically require crosslinking or reinforcement with biomaterials to achieve sufficient mechanical strength for load-bearing applications, such as hydroxyapatite which constitutes 65-75% of human bone mass.

Chitosan, derived from chitin deacetylation, exhibits favourable properties for antimicrobial activity and controlled degradation. Genipin-crosslinked chitosan scaffolds demonstrate extended degradation times of up to 20 weeks while maintaining biocompatibility comparable to collagen, making them particularly suitable for guided tissue regeneration where sustained and reliable structural support is required.

Synthetic Polymers: Tunable Properties

Synthetic polymers provide precise control over molecular weight, degradation kinetics, and mechanical properties. Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), and their copolymer poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) dominate tissue engineering applications due to FDA approval and well documented degradation pathways.

Degradation rate and required properties in PLGA can be adjusted with the ratio of L-lactide and G-lactide. Glyconic acid accelerating degradation in short-term scaffold whilst lactic acid extends for long-term support. In this case there is an additional factor to consider which is acidic degradation which can cause inflammation locally if proper scaffold design doesn’t allow the body to remove it.n.

Working on the medical material database at Ansys, since the beginning of this month now part of Synopsys I curated several biomaterials for the addition of new medical devices. In doing so I have identified over 100 medical devices utilising polymer scaffolds made of Poly(D,L-lactide) (PDLLA) offering an amorphous, rapid-degrading flexible structures.

Whilst PLLA is an industry standard with highly documented use and a semi-crystalline rigid structure, PDLLA has only recently started seeing significant medical use. On this project I identified the widespread use of PDLLA and added it to the medical materials database.

Fabrication Techniques

Freeze-Drying (Lyophilisation) procudes porous scaffolds are created by freezing a polymer followed by sublimation under a vacuum leaving very dense porous networks. It takes significant time and energy and typicall produced on a small scale.

Electrospinning produces nano or micro-scale continuous fibers, fibrous scaffolds closely mimic the extracellular matrix in tendons and similar tissues. The high surface area to volume ratio promotes cell attachment but small pore sizes can limit cell infiltration.

3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing enable scaffold fabrication with precise control over internal structures, fused deposition modeling (FDM) can be used but the orthotropy introduced by layer interfaces needs to be considered as well as layer adhesion reducing mechanical performance with likelihood of shear failures. Stereolithography (SLA) uses photopolymerisation by selectively crosslinking a light sensitive liquid resin using UV light, proteins and peptides can be mixed directly into this resin.

Bioactive Scaffold Design

Advanced scaffolds incorporate growth factors, drugs, or bioactive molecules to actively promote tissue regeneration. Surface functionalisation with peptides enhances cell adhesion through integrin binding. Composite scaffolds can also be integrated with ceramics such as hydroxyapatite to provide osteoconductivity and mechanical support to match that of natural bone.

Conclusion

Polymer scaffolds represent an integral part of tissue engineering, polymers and different fabrication techniques allow incredible versatility by tailoring geometry, materials and bio-active compounds to match the required mechanical properties and degradation of the patient and application. As manufacturing, polymer and understanding of cellular responses advances polymer scaffolds will become increasingly biomimetic to seamlessly integrate with the body’s regenerative processes.

Further Reading

Further work on 3D printed polymer lattices in my 3rd Year Undergraduate Dissertation. Applied in gear weight saving for powered knee orthosis. Includes lattice and material characterisation using several methods and merges functionally graded triply periodic minimal surfaces with topology optimisation to produce a variable infill.